Words the Irish Gave the English Language

Do you know that a lot of currently trendy words have an Irish origin? “Dystopia”, a term used in TV shows, in world politics and, quite possibly, the imminent future could be one. It was coined as the opposite of Utopia, by the philosopher John Stuart Mill, when describing the plight of Irish tenant farmers to the English parliament in 1868. Another word is “boycott”, bandied about today as part of the trend for trade wars and activism, has its roots in those same tenant farmers refusing to pay rent to their county Mayo landlord, Charles Boycott in 1880.

There are plenty of words and phrases too originating in the Irish language, which have made their way into standard English use. It is one of the beauties of English, that it takes words from other languages and melds them into popular, everyday use. Let’s take a closer look at some of these words and see how the English language is always adopting and adapting in order to survive and grow.

Photo via EveryStockPhoto

Fun Galore

Coming from the Gaelic go leoir meaning plenty, enough or more than enough, and combine the sounds and take a look at what you get! “Galore” is a great word to throw into a sentence, such as “there were people galore at the party” in a way that breaks the rules of grammar. It seems to suggest fun and excess but not so much that it could be a bad thing. The book Whisky Galore by Compton McKenzie uses the word in its true fashion, implying that great fun was to be had with all that free booze.

Whiskey to be savoured

Speaking of booze, “whiskey” with an ‘e’ is another word coming from the old Irish into everyday use; without the ‘e’ the drink becomes scotch. Uisce beatha or “water of life” in translation, was mispronounced enough to become whiskey as we know it today. The strong spirit, distilled traditionally in the north and south of the country, was believed almost to have a life of its own. Those who drank it certainly felt an oomph from the first couple of sips. Poitin, a sister drink of whiskey, and one on the wrong side of the law, tends to do more damage than good, however.

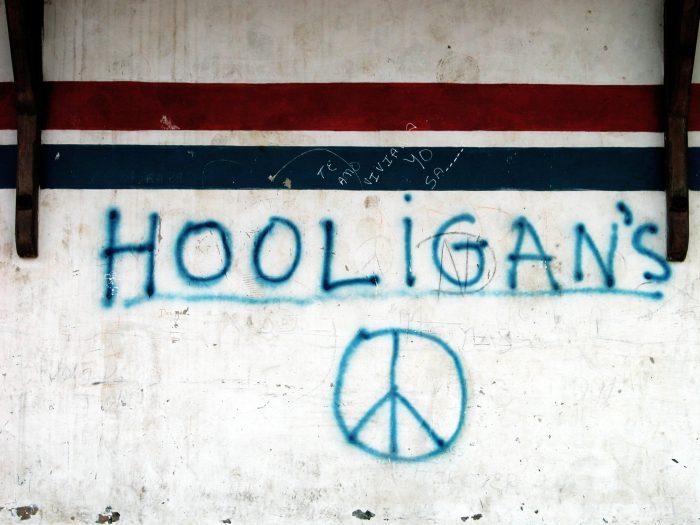

Hooligans the lot of them!

Possibly closely connected with the consumption of whiskey and its illegal relation is the rise of “hooligan” as an English word. It comes from the family name of O’Houlihan, spelled O’hUallacháin in Irish, with a guttural emphasis on the ‘ch.’

Photo via EveryStockPhoto

A popular music hall song of the late 1800s referenced the Irish fighting family of O’hUallacháin, who were known for their bad social behaviour. The surname was anglicised to “hooligan” and still lives on today in the dreaded football hooligan, a popular target of the English tabloid press. I’ve known a few O’Houlihans in my time and all of them lovely people, I have to say.

Photo via EveryStockPhoto

Brogue, more than just a shoe.

An obvious one to all of us Irish speakers. “Brog” is the Gaelic for shoe and is probably one of the first words we learn when going to school. Traditionally a brogue is a tough, hard-wearing shoe worn by country people and those who couldn’t afford a gentler one for wearing about town. The design and toughness of the brogue lead to its attraction and to it becoming the respected item of fashion it is today. The shoe was probably developed for those who worked outdoors and needed a hard-wearing piece of footwear, which could be easily repaired at home. It is said that the holes which decorate the leather once went fully through and were to allow the shoe to drain when walking in the bogs.

Dig it?

I’m not entirely convinced on this one, though the case is strong enough on the surface. Tuig is the Irish verb for “to understand”. Tigim or just tig is very popular among native speakers, as it means “I understand” or “ok”. Looking at the words “dig” and tig, the spelling and pronunciation are very similar, but how an Irish everyday term became one of the best-known phrases of the ‘60s counter-culture isn’t quite obvious. Timothy Leary was born in Springfield, Massachusetts though, home to many Irish immigrants, especially Irish-speaking Blasket Islanders. Could the ‘60s guru have heard it when growing up. Who knows, man?

Sin É (that’s all folks, in Irish)

All in all, English is a wonderful language. It takes from its surroundings, and without a governing body, it grows unhindered. Its connections with colonialism are obvious, but it is the only truly world language. English is always developing and changing and taking on new words daily. How many popular English words can you think of that came from elsewhere?