Name changes may be forced by new Chinese rules

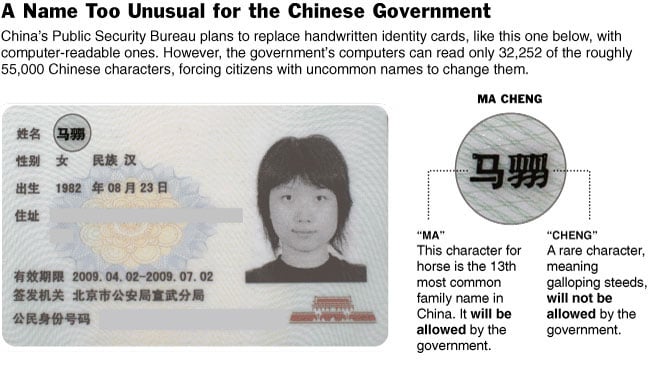

The Chinese government has been reported to have plans to release a list of about 8,000 characters that they recommend be used for everyday purposes, including textbooks, documents, and names for newborn babies. Limitations in updating technology to recognise all of the roughly 55,000 Chinese characters in existence means that it is very difficult for the government to implement nationwide electronic ID cards, as well as digitisation of texts. Their solution, rather than adding thousands of characters that most people will never use, is to restrict new baby names, as well as require people with very unusual names to change them.

The Chinese government has been reported to have plans to release a list of about 8,000 characters that they recommend be used for everyday purposes, including textbooks, documents, and names for newborn babies. Limitations in updating technology to recognise all of the roughly 55,000 Chinese characters in existence means that it is very difficult for the government to implement nationwide electronic ID cards, as well as digitisation of texts. Their solution, rather than adding thousands of characters that most people will never use, is to restrict new baby names, as well as require people with very unusual names to change them.

Everyday Chinese involves about 3,500 characters, and the recommended 8,000 simplified characters are reportedly enough to convey “almost any concept in any field”. This doesn’t bode well for the some 60 million Chinese people with obscure names, who may have to choose simpler names in order to receive the mandatory ID cards.

Government officials suggest that names have gotten out of hand, with too many parents picking the most obscure characters they can find or even making up characters, like linguistic fashion accessories. But many Chinese couples take pride in searching the rich archives of classical Chinese to find a distinctive, pleasing name, partly to help their children stand out in a society with strikingly few surnames.

By some estimates, 100 surnames cover 85 percent of China’s citizens. Laobaixing, or “old hundred names,” is a colloquial term for the masses. By contrast, 70,000 surnames cover 90 percent of Americans.

At last count, China’s Wangs were leading with more than 92 million, followed by 91 million Lis and 86 million Zhangs. To refer to an unidentified person — the equivalent of “just anybody” in English — one Chinese saying can be loosely translated this way: “some Zhang, some Li.”

While I don’t agree with people having to change their names for the sake of convenience for the government, cultures that have an alphabet-based written language can’t compare to this situation. In English, we have our standard 26 letters, along with numbers, and various punctuation marks. We occasionally adopt accent marks when we borrow from other languages. In Chinese, the computer systems must recognise thousands upon thousands of characters. Many countries also forbid parents to name their children potentially offensive or damaging names, and names with numerals in them have been denied (such as baby 4Real, who was later named Superman).

I think it would also be quite frustrating not being able to input one’s own name on a computer, or have to describe it to someone who had never even seen the character before, but then again, both my English and Chinese names are pretty common.

Full article from NYTimes.com.